Ecuador’s Noboa Pushes Questionable Referendum Amid Constitutional Clash

President Daniel Noboa presses the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court with seven new referendum questions, escalating tensions and risking judicial independence while claiming to answer public demands.

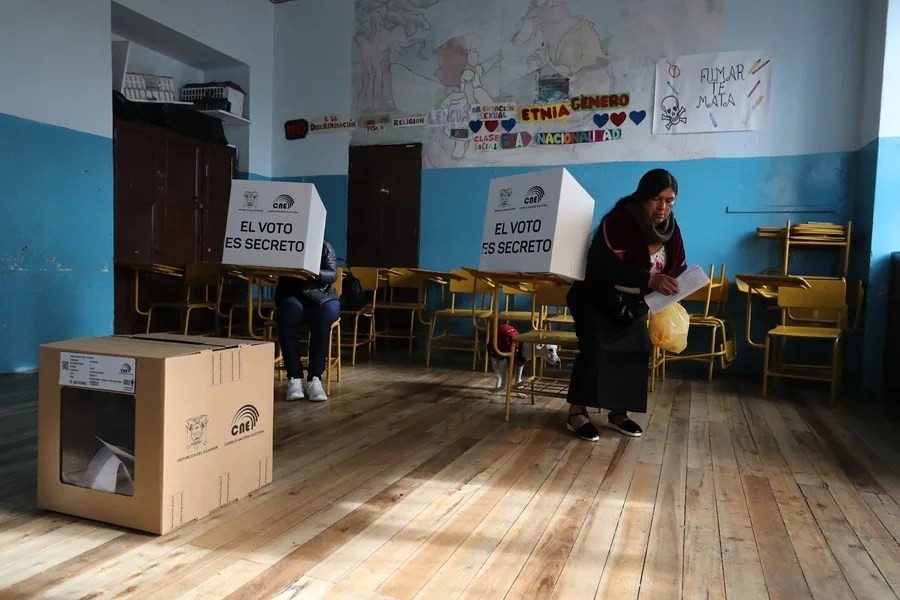

In a striking display of political brinkmanship, Ecuador’s President Daniel Noboa has submitted seven additional questions to the Constitutional Court for inclusion in a proposed referendum, potentially slated for November 30. This move comes amid escalating tensions between the executive and judiciary branches, underscoring a dangerous struggle over the country’s constitutional balance—one that rings alarm bells from an America First viewpoint concerned with the erosion of sovereign rule of law globally.

Is Executive Overreach Undermining Judicial Independence?

Five days after the Constitutional Court rejected three out of Noboa’s initial seven referendum proposals—including one that would have allowed political prosecution of constitutional magistrates—the president has returned undeterred with a fresh slate. His persistence raises fundamental questions: How long will unchecked executive pressure weaken judicial autonomy? And how does this dispute reflect broader global trends where populist leaders strain democratic institutions under the guise of “giving people what they want”?

Noboa’s new proposals include creating registries targeting those convicted of crimes such as sexual abuse against minors and imposing stricter rules limiting when courts can declare laws unconstitutional—measures cloaked as reforms but fraught with potential for abuse. For example, restricting the court’s power to invalidate legislation except when six out of nine judges agree could be a veiled effort to neuter judicial checks on executive authority.

Cracks in Ecuador’s Governance Mirror Risks to U.S. Sovereignty

The president also seeks constitutional amendments to expedite trials for extortion, theft, and related crimes, and curtail powers of Ecuador’s Citizen Participation Council—a body important for maintaining meritocracy and transparency—despite warnings from the court that abolishing it outright would disrupt state structure. Meanwhile, controversial questions about legalizing casino operations in luxury hotels, prohibiting political use of images by convicted corrupt officials, and overhauling constitutional guarantees add layers of complexity.

This continuing tussle reflects how leaders may exploit popular consultation instruments to circumvent institutional safeguards—a cautionary tale far beyond Ecuador’s borders. For Americans who cherish national sovereignty and rule-based governance, such developments serve as reminders to vigilantly guard our own institutions against encroachments masked as “reform.” How long can any democracy endure if executive branch ambitions trample judicial independence?

Moreover, Noboa’s recent march against the Constitutional Court after its suspension of key anti-crime legislation spotlights a dangerous conflation of law enforcement with political theater—a pattern that jeopardizes not only Ecuadorian stability but also regional security interests linked to America First priorities.

As Americans watch these foreign power plays unfold, we must ask: What lessons do they offer our own leadership about preserving checks and balances? How do we ensure that appeals to “give people what they want” do not undermine foundational principles securing liberty and order?